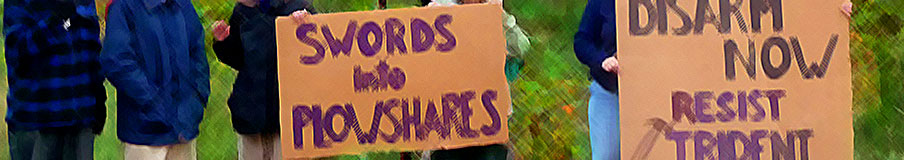

Often when we are meeting with people and telling them about our Disarm Now Plowshares witness, we are asked: “What can we do to support and help you?” Everyone who asks is sincere, thoughtful and compassionate. When I look around the room, I see that they have careers, jobs, family, school, plans for doing this project and that project–and where is there room for peacemaking? We have to expect peacemaking to disrupt our lives. What comes to mind is this short reflection of Daniel Berrigan: The Price of Peacemaking.

Susan Crane

The Price of Peacemaking by Daniel Berrigan

We have assumed the name of peacemakers, but we have been, by and large, unwillingly to pay any significant price. And because we want the peace with half a heart and half a life and will, the war, of course, continues. War, by its nature, is total-but the waging of peace, by our own cowardice, is partial. So a whole will and a whole heart and a whole national life bent toward war prevail over the verities of peace.

In every national war since the founding of the republic we have taken for granted that war shall exact the most rigorous cost, and that the cost shall be paid with cheerful hearts. We take it for granted that in wartime, families will be separated for long periods, that people will be imprisoned, wounded, driven insane, killed on foreign shores. In favor of such wars, we declare a moratorium on normal human hope-for marriage, for community, for friendship, for moral conduct toward strangers and the innocent. We are instructed that deprivation and discipline, private grief and public obedience are to be our lot. And we obey. And we bear with it-because bear we must-because war is war, and good war or bad, we are stuck with it and its cost.

But what of the price of peace? I think of the good, decent, peace-loving people I have known by the thousands and I wonder. How many of them are so afflicted with the wasting disease of normalcy that, even as they declare for peace, their hands reach out with an instinctive spasm in the direction of their loved ones, in the direction of their comforts, their homes, their security, their incomes, their futures, their plans—that five-year plan of studies, that ten-year plan of professional status, that twenty-year plan of family growth and unity, that fifty-year plan of decent life and honorable natural demise.

“Of course, let us have the peace,” we cry, “but at the same time let us have our normalcy, let us lose nothing, let our lives stand intact, let us know neither prison nor ill repute nor disruption of lives.”

And because we must encompass this and protect that, and because at all costs-at all costs- our hopes must march on schedule, and because it is unheard of that in the name of peace a sword should fall, disjoining that fine and cunning web that our lives have woven, because it is unheard of that good men and women should suffer injustice or families be sundered or good repute be lost-because of this we cry peace and cry peace, and there is no peace.

There is no peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war–at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison and death in its wake.

Filed under: Historical writings | Tagged: Daniel Berrigan, disrupted life, good repute, price of peace, Price of Peacemaking, prison witness |

Reading this is both challenging and en-courage-ing. I hope it stays up here a long time, so I can reread it and reread it so it becomes more a part of me.

There is only one phrase that kind of sticks in my throat: “their hands reach out with an instinctive spasm in the direction of their loved ones.”

Surely loved ones belong in a different category than “comforts, homes, security, incomes, futures, plans…”? I hope to grow in detachment from things, but not from people.

After all, isn’t love for loved ones what teaches us empathy for those who lose their loved ones due to war, injustice, violence?

I understand and agree that we can’t keep a vise-grip on each other, or let family ties suffocate who we are created to be. But I couldn’t agree with anything on this blog if I wasn’t sure that working for peace deepens rather than disrupts our love for one another.

I guess I look at it this way.

The love we have for family and friends shouldn’t hold us back from struggling (out of love) for the common good.

Many of the people in Germany during WW II who hid dissidents, gays or Jews did it despite having families and children. Of course they loved their children, but they felt compelled by their conscience to help others, even if it meant putting their family at risk. And we know many others wouldn’t take any risk because they didn’t want to put their family in danger. Susan

[…] decisions based on fear or based on our conscience and faith? We aren’t going to have peace until we are willing to risk as much for peace as the warmakers are willing to risk for war. Time for a Farewell to […]

[…] decisions based on fear or based on our conscience and faith? We aren’t going to have peace until we are willing to risk as much for peace as the warmakers are willing to risk for […]